Numbers don’t lie but it sure can be deceiving – The Bronze Alchemist

No, it’s not a “thing” of mine to start the post with a quote. But if I can summarize this post in one sentence, it would be what I mentioned above. Let’s say you have an investment portfolio worth $100,000 and it gave you a return of $10,000 in the year, then you have earned 10% (actual return / portfolio value). Your asset “manager” (fund house, bank, debtors etc.) will acknowledge over an official looking transcript that you have earned 10% on your overall portfolio. There is no doubt on the amount you have earned; the return number on this transcript is as true as the sun in the sky. You are basking in the full shine (returns) of the sun (your portfolio) and it’s making you warm.

However, as it always happens, there are some dark clouds in the sky, preventing you from benefiting from the full warmth of your returns. This dark cloud, Inflation, is one of the most significant risk affecting your future returns.

There are many factors to consider, but for this post and for all practical purposes,

Real rate of return ≅ Nominal rate of return – Inflation rate

i.e., to calculate your real returns from assets, you have to subtract the returns from the official looking transcript for inflation adjustments. ( In case of deflation, you add the rate to your returns ).

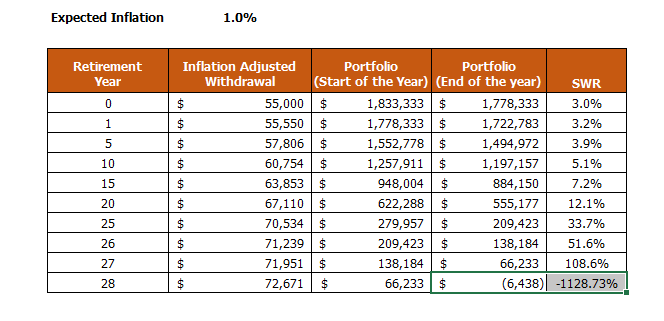

In the previous post, I showed you how inflation can throw a wrench in your retirement plans. This post on real returns could be considered an addendum to the previous post; and to serve a reminder: consider all factors a.k.a “risks” on the returns. Simply put, in 2015

- If there were a 2% inflation in your country, your real return is 8% (10% – 2%) or only $8000 and not $10,000

- For 5% inflation, real return is is 5% (10% – 5%) or only $5000 and not $10,000

- For 10% inflation, real return is 0% (10% – 10%) or $0 and not $10,000

- For 11% inflation, real return is -1% (10% – 11%) or -$1000 and not +$10,000

I know you are good at mathematics and can do basic calculations; but I cannot emphasize the above point enough. You lose money to inflation, for no fault of your own as an individual, just for having the privilege to be part of your country’s economy. Keep in mind that when I say -$1000, no one is going into your bank and take $11,000; your economy does it. So that’s why the numbers can be deceiving. You have $10,000 worth of money in your bank but you have to pay extra $1000 to be able to buy a group of items for which you paid $10,000 a year before. If this statement seems confusing, take a look at my previous post on inflation or search for it on the web.

Ideally, your choice of asset class should be able to provide you inflation beating returns. In terms of Safe Withdrawal Rate or SWR, if you have a specific percentage, say 3%, you have to make sure that the nominal return is at least 3% (or 300 basis points) above inflation rate. If inflation is 5%, you need 8% returns. But if inflation is 0%, you only need 3% returns. If there is a -1% inflation (or 1% deflation), you only need 2% returns. You get the picture.

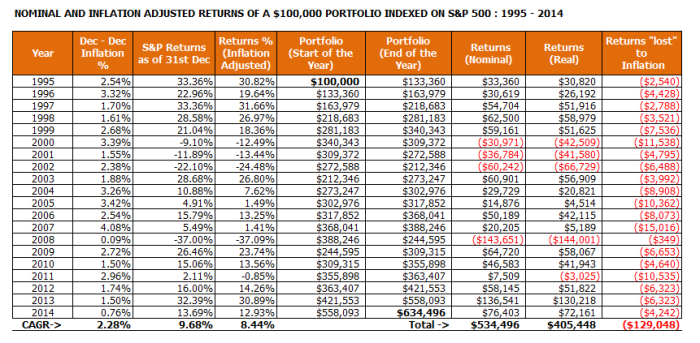

Enough of this monkey business! Nothing hits harder than the truth so let’s look at some actual numbers. I did a simple projection of calculating USA’s S&P 500 index performance from 1995 to 2014 (20 years) with and without inflation adjustment. I assumed my initial portfolio value to be $100,000 that I will invest in a strict S&P 500 indexed fund on Jan 1, 1995. I am not adding any subsequent amounts to the portfolio, just letting the market do the work for me. Look at the results below:

Source:

Inflation: http://www.inflation.eu/inflation-rates/united-states/historic-inflation/cpi-inflation-united-states.aspx

S&P historical performance: https://ycharts.com/indicators/sandp_500_total_return_annual

My $100,000 portfolio has grown to $634,496 by the end of 2014. However due to inflation, the actual value of my portfolio in today’s dollars is worth only $505,448, losing almost 1/4th of the portfolio value (a factor of 1.2905 to be exact). And you know what the bad thing is? I cannot do anything about it. In fact, I should consider myself lucky to have invested in S&P 500. If I had invested in Certificates of Deposits (CDs), T-Bills or other bonds, I would have been barely able to improve my portfolio, definitely not to the tune on the amount returned by S&P 500. What if I were paranoid about the stock market and just hoarded all $100,000 under my mattress? Well, that would have yielded only $55,000 worth purchasing power in today’s dollars.

With regard to the point I am trying to make – use real return rate in SWR calculation – all is fine and dandy, except for one small issue: inflation lags behind by the unit of time that takes for your government to publish inflation rates. In USA, you can get monthly rates, so it is easy to adjust if you want to do it monthly. Yearly adjustment would do just for USA, the inflation rates are relatively steady in this part of the world.

My point, keep it real.

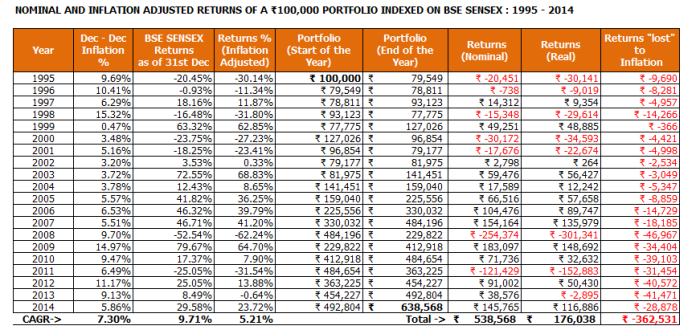

As a bonus, I am presenting below the projections from India to understand how things are with good developing economies. India is part of the BRICS bloc (Brazil, Russia, India, China and South Africa). Indian economy developed rapidly in the past two decades thanks to IT boom and then later to manufacturing boom. I used BSE SENSEX as the benchmark index and started with ₹100,000 portfolio. As per the data, I lost over 67% of the returns to inflation or by a factor of 3.6253 for every rupee. Wow! Although, the ETFs in India don’t do as well as actively managed funds over there. It’s possible to have better returns using good and stable active mutual funds, good blue chip stocks or if money were invested in real estate; the valuations growth were phenomenal in the past 20 years.

How about this for an observation?

Even though the average#1 returns from India was 9.71% over the 20 years, because of the average#1 inflation of 7.3%, the average real rate of return was only 5.21%. Compare that to USA’s, whose average#1 returns were only 9.68% However due to average#1 inflation being only 2.28% over 20 years, the average return came out to 8.44%; better than India’s. Warning: Things are never as simple as this in real, there are many complex factors to consider, and whatever adjustments we make, we always end up comparing apples to oranges.

Source:

Inflation: http://www.inflation.eu/inflation-rates/india/historic-inflation/cpi-inflation-india.aspx

BSE SENSEX historical performance: http://www.bseindia.com/indices/IndexArchiveData.aspx

#1Compounded Annual Growth Rate or (CAGR) is calculated by the formula

CAGR = [(Final value/Initial value) ^ (1/number of time periods)] – 1

For example, with initial value ($100,000) and final value ($634,496), this would be 9.68%. In excel you would use this formula “=RATE(20,0,-100000,634496)”

You must be logged in to post a comment.